Touching Grass is Good For You — LiterallyJan 14

people online are walking around barefoot for their health and selling infrared mats for $700. science suggests “grounding” isn’t as crazy as it sounds

Riley NorkI’ve covered Casey Newton’s activism for a little over a year, and in that time I’ve learned to read his reporting through a lens of tremendous, committed bias. Even still, I assumed Substack had a Nazi problem when he reported Substack had a Nazi problem, as the exaggeration of such a tremendous claim really did seem to me, earlier this week, unthinkable. Then I read Jesse Singal’s great piece on the topic, which contextualized all of Newton’s claims to the point of — I would argue — an almost total debunking. In the piece, Singal referred back to the root of Substack’s Nazi phantom menace several times, which was not first born in Newton’s self-indulgent fantasies, but in the Atlantic, where Jonathan M. Katz initially charged the company with platforming a large and growing American Nazi movement.

Here, in an important piece that first appeared on Singal-Minded, Singal’s great Substack, Jesse turns over every single rock in the argument, thoroughly investigates the author’s claims, and lays the subject to rest. A definitive account of media malfeasance.

-Solana

A fairly contrived effort to endlessly link the word Substack to the word Nazi has had some moderate success, unfortunately. Or at least enough success to have sparked an open letter republished on many individual Substacks calling on Substack to get rid of Nazis, a counter–open letter calling on it to maintain its liberal content-moderation standards, a statement from Substack co-founders Hamish McKenzie, Chris Best, and Jairaj Sethi explicitly stating that they do not plan to ban Nazis from the platform, a bunch of Substackers responding by leaving or threatening to leave if Substack doesn’t moderate the content it hosts more aggressively, and a spate of news coverage of all of the above.

This is all pretty odd given that Substack’s content guidelines are conspicuously written to hew quite closely to the First Amendment on matters of alleged hate speech and have been in place for more than two years. Plus, the site’s founders have been very consistent about their lack of interest in adopting a more conservative approach to speech on Substack, even when sticking to their guns has led to bad PR. Since it’s clear that on Substack, almost anything goes that doesn’t involve a credible threat of violence, no one should be surprised that unsavory types can set up shop here.

Earlier this week I critiqued the reporting of Casey Newton, arguing that his work on the controversy for his publication Platformer was shoddy and misleading, and seemed designed to obscure key information from his readers. At the end of the day, after what Newton described as a rather comprehensive search for extremist content on Substack, he and his team sent the company a grand total of six publications they believed violated its standards, and Substack banished five of them while declining to actually change its written policies. The publications in question, Substack told Newton in a statement, had 100 active readers between them and none had paid subscriptions turned on. Newton quoted selectively from Substack’s response, in a manner that excluded the number of Substacks he had reported, their moribund nature, and their lack of paid readership. When I asked Newton why he had left out this information, his answer — that revealing how many Nazi publications his team reported to Substack would put him and his team at risk of harassment at the hands of the Nazi authors in question — didn’t really make sense, and he wouldn’t elaborate on it. (Newton has since announced Platformer is leaving Substack.)

In this post I’d like to focus mostly on the article that started this whole affair: Jonathan M. Katz’s late November piece in The Atlantic, “Substack Has a Nazi Problem.” It turns out Katz almost entirely fabricated what is perhaps his most damning anecdote about Substack’s approach to extremism. After I lay out, in detail, how he did this, I’ll explain how The Atlantic (and Katz) responded to my critique. Then I’ll close with a discussion of the difficulty of developing consistent content moderation guidelines, drawing on several Substack competitors’ deeply troubled attempts to do so.

To repeat a disclosure I tucked into a footnote in my last post: two Substack products — this newsletter and the podcast I co-host, Blocked and Reported — generate the vast majority of my income. Back in 2021, Substack gave Katie Herzog and me an advance to move our podcast Blocked and Reported from Patreon to Substack. That yearlong agreement has since lapsed. These days, Substack is providing us with some support finding advertisers and coordinating ad buys as part of an experimental pilot program as well as ongoing access to Getty Images until later this year, but beyond that we are operating under the same agreement as anyone else and paying the normal 10% cut of our gross revenue to the company. This newsletter, meanwhile, never received any direct support from Substack, other than access to Getty, which, if memory serves, I asked Substack to tack on to our BARPod arrangement. All that said, Substack is built in a manner that allows me/us to take my/our subscribers elsewhere if we so choose, so there’s no sense in which I am bound to this platform. I should have also noted in my last article: I do feel a sense of loyalty to Substack because of the salutary effect it has had on my career, and I think McKenzie and Best are good guys (I’m not mentioning Sethi solely because I haven’t really talked to him much). It’s your right as a reader to know that and to judge what follows accordingly. (Correction: I did mention my sense of loyalty to Substack in the prior article! My mistake.)

I’ll have to grapple with another instance of my own bias to even engage in this discussion. Katz, who had a Substack himself until he announced his departure today, is apparently a well-regarded author. But he is also, in my brief and exceptionally unpleasant interactions with him, an erratic and toxic individual, at least when it comes to hunting down and attempting to punish his perceived enemies of justice. My most memorable run-in with Katz occurred when he screenshotted a tweet of someone saying that my death should be toasted with champagne, and described it as “one of the truest things ever written” on Twitter.

So I should acknowledge my bias: going in, I did not trust Jonathan Katz to give a dispassionate account of Substack’s “Nazi problem.”

That out of the way, here’s the meat of Katz’s argument:

Substack, founded in 2017, has terms of service that formally proscribe “hate,” along with pornography, spam, and anyone “restricted from making money on Substack”—a category that includes businesses banned by Stripe, the platform’s default payment processor. But Substack’s leaders also proudly disdain the content-moderation methods that other platforms employ, albeit with spotty results, to limit the spread of racist or bigoted speech. An informal search of the Substack website and of extremist Telegram channels that circulate Substack posts turns up scores of white-supremacist, neo-Confederate, and explicitly Nazi newsletters on Substack—many of them apparently started in the past year. These are, to be sure, a tiny fraction of the newsletters on a site that had more than 17,000 paid writers as of March, according to Axios, and has many other writers who do not charge for their work. But to overlook white-nationalist newsletters on Substack as marginal or harmless would be a mistake.

At least 16 of the newsletters that I reviewed have overt Nazi symbols, including the swastika and the sonnenrad, in their logos or in prominent graphics. Andkon’s Reich Press, for example, calls itself “a National Socialist newsletter”; its logo shows Nazi banners on Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, and one recent post features a racist caricature of a Chinese person. A Substack called White-Papers, bearing the tagline “Your pro-White policy destination,” is one of several that openly promote the “Great Replacement” conspiracy theory that inspired deadly mass shootings at a Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, synagogue; two Christchurch, New Zealand, mosques; an El Paso, Texas, Walmart; and a Buffalo, New York, supermarket. Other newsletters make prominent references to the “Jewish Question.” Several are run by nationally prominent white nationalists; at least four are run by organizers of the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia—including the rally’s most notorious organizer, Richard Spencer.

Right off the bat, Katz disseminates a false claim about Substack’s moderation policies. It is false that anyone who is “restricted from making money on Substack” is banned from using the platform. Katz might have been genuinely confused here given that there’s some ambiguity to that passage of Substack’s content policies, which is subheaded “People restricted from making money on Substack.” If read hastily, this could be interpreted in the manner Katz is describing — these people are banned from posting to Substack, full stop. But in full context, it seemed a lot more likely to me that Substack was simply saying that if you’re banned from Stripe, you can’t monetize your content on the platform. I confirmed this with Substack. Surely Katz could have done so too, but he appears not to have checked. (I asked McKenzie and Best if Katz had asked about this, but they declined to reveal details of their interactions with him. We’ll get to Katz’s and The Atlantic’s responses below.)

This might seem like a somewhat minor or nitpicky issue, but it bears on what is probably the most troubling story in Katz’s article, and the part of it that seems to have gone the most viral. It has since been updated slightly — we’ll get there — but here’s how it initially read:

The platform has shown a surprising tolerance for extremists who circumvent its published rules. Patrick Casey, a leader of Identity Evropa, a defunct neo-Nazi group, had been banned from Twitter and TikTok and suspended from YouTube after running afoul of those platforms’ terms of service. (Elon Musk, Twitter’s owner, subsequently announced an “amnesty” that restored Casey’s account, among others.) Perhaps most damagingly to a content creator, Stripe had prohibited Casey from using its services.

But Substack was willing to let a white supremacist get back on his feet. Casey launched a free Substack newsletter soon after the 2020 election. Months later, he set up a paywall, getting around Stripe’s ban by involving a third-party payment processor. “I’m able to live comfortably doing something I find enjoyable and fulfilling,” he wrote on his Substack in 2021. “The cause isn’t going anywhere.” Casey’s newsletter remains active; through Substack’s recommendations feature, he promotes seven other white-nationalist and extremist publications, one of which has a Substack “bestseller” badge.

It’s a very troubling story: a white nationalist who had been otherwise banished from polite online society and largely cut off from monetizing his noxious content had touted Substack as allowing him to “live comfortably doing something I find enjoyable and fulfilling.” So it’s no surprise that the tale got repeated endlessly via the open letter disseminated by Substack’s critics, in which it was mentioned very early on. These claims were spread by Substackers like Margaret Atwood, Daniel Drezner, Kevin Kruse, Tom Scocca, and many others. No one appears to have fact-checked them, perhaps because 1) everyone assumed The Atlantic did, and 2) no one fact-checks anything when it comes to signing or disseminating open letters birthed by moral panics.

I found the story odd, because if you go to Patrick Casey’s page, which points readers to his publication, Restoring Order, you’ll see he is listed as having 800 subscribers. When Substack lists an individual’s or publication’s number of subscribers, that includes both free and paid ones, combined, in the case of users who have turned on monetization. (I’m not going to link directly to Casey’s work, but I’m including the name of his publication so readers will have enough information to do their googling and fact-check my claims if they so choose.)

This confused me, because no one is “liv[ing] comfortably” on 800 total subscribers. Conversion rates from free to paying subscribers vary greatly on Substack, but figures like 5% or 10% are not unusual. And Casey lacks the badge awarded to authors with at least “hundreds of paid subscribers,” meaning this also isn’t an outlying instance of a writer with a relatively small following but a sky-high conversion rate.

Some very simple googling solved the mystery and proved that basically every element of Katz’s story about Patrick Casey is false. In just two paragraphs, Katz falsely accuses Substack of tolerating the violation of its policies on the part of a white supremacist, falsely claims Casey was able to make a comfortable living on Substack, falsely (and strongly) implies that Casey set up a paywall on Substack when he should have been banned from doing so, and falsely portrays Casey’s “The cause isn’t going anywhere” quote as though it has anything to do with Substack, which it didn’t.

All this becomes very clear, very quickly, when you simply read the Patrick Casey post Katz is quoting from, which Katz doesn’t link to. It doesn’t appear to exist in live form anywhere online, but here’s the full text from an archived version with the two bits Katz quoted bolded by me. (I’d normally remove links to a white supremacist’s online accounts, but all the below links are to archived versions of the pages in question, so I’ll just leave them intact.)

A Few Updates

Updates on my life, thoughts on where we are, and my plans for this Substack.

[photo of Casey I can’t indent]

Patrick Casey

Oct 24, 2021

It’s been some time since I updated my Substack, which I created in November 2020. This was during the early phases of the contested election, when, despite the odds, it seemed as if a Trump victory was still possible.

That was nearly a year ago — and much has changed since. Year one of the Biden administration has been predictably terrible for anyone concerned with the border crisis, medical tyranny, anti-white indoctrination, the repression of dissent, and a whole host of other issues. While midterms will likely go well for Republicans, I’m not holding my breath for any significant change to occur as a result. 2024 should be interesting, but frankly, barring unforeseen events, which admittedly do play a primary role in dictating the flow of history, I’m not expecting much. So while I’m pessimistic in the short term, I remain a long term optimist. We’re going to win, but we really have no idea how it’s going to happen.

Personally, I continue to suffer from censorship and deplatforming, having lost accounts on both Trovo and Twitter. YouTube is thus the only major platform on which I have an account, but my channel is currently on timeout for 90 days. The infraction? Medical disinformation. While I can use the account again in November, after one more strike it will be terminated. As such, I’ve created an Odysee account, where you can find the archive of Restoring Order episodes. A silver lining to all of this, though, is that it has forced me to reconsider my role in politics beyond being an “influencer” or content creator, which, long term, might be for the best.

Aside from the unfortunate realities of deplatforming, my life is going fairly well. I’ve been blessed with a growing network of friends and political contacts, I’m in great health, and I’m able to live comfortably doing something I find enjoyable and fulfilling. Again, long term I’ll likely have to find something else to do, but I’m more than content doing this for now.

I do plan to use this Substack more often for both paywall and non-paywall posts. Given that I’ve been banned from Stripe, which Substack uses for its paid subscriptions, half of each paywall post will be available on Substack, while the other half will be accessible via SubscribeStar.

Lastly, I sincerely hope that everyone reading this has been able to stave off any feelings of despair or hopelessness that may have arisen in the wake of Biden’s inauguration. It’s perfectly normal to check out from politics for a while if needed. However, we mustn’t forget that we all have a role to play in our eventual victory, however seemingly slight or insignificant. Spread the message on social media, create content, support content creators and activists, get active in local politics, and, above all else, ensure that you’re taking the necessary steps to achieve your goals. If you’re obese, addicted to substances, lacking good career prospects, or failing to take steps to create a family, then you should fix these problems first and foremost before trying to save the world. The cause isn’t going anywhere — remember that.

It’s pretty clear, in context, that Casey was not saying that his “comfortable living” came from Substack, given that he couldn’t make any money off of Substack! Rather, this referred to some other source of income. Casey confirmed this when I emailed him, and you don’t need to take his word for it, because again, we know that he has a paltry 800 total Substack subscribers — information Katz surely could have found and shared with his readers had he chosen the path of competent and transparent journalism.

What of the claim that Substack allowed Casey to “circumvent its published rules”? Katz doesn’t explicitly explain what he means, but in context it’s clear that he must be saying that because of his Stripe ban, either Casey shouldn’t have been allowed on Substack at all, or he shouldn’t have been allowed to monetize on Substack.

Both claims are false or misleading. The first stems from Katz misunderstanding and misreporting Substack’s content policies, which I’ve already explained. Nothing in Substack’s rules would have banned Casey from hosting a free Substack solely because he was banned by Stripe.

If Katz meant that Substack allowed Casey to “circumvent” the platform’s rules by monetizing on Substack despite the Stripe ban, then yes, Substack would have been allowing a white supremacist to circumvent its rules. That seems to be what he’s saying, because Katz writes that Casey “g[ot] around Stripe’s ban by involving a third-party payment processor.” I really think any reader is going to read this as though Casey monetized on Substack via this supposed third-party payment processor — otherwise, why would Katz include this detail?

But this is clearly false as well. As you can now see by reading the above excerpt, Casey was linking out to an entirely different platform, SubscribeStar, at the time. Of course Katz’s criticism of Substack here would have been far weaker if he said something like “Casey was banned from monetizing on Substack, so he linked out to a different site that had more lax monetization policies.” As the line “half of each paywall post will be available on Substack, while the other half will be accessible via SubscribeStar” tells us, Patrick Casey’s monetized content did not exist on Substack. Katz knew all this, given that he quoted from the archived post and therefore must have read it. But he simply left out those details. This is extremely dishonest journalism.

It’s also clear that Katz attempted to trick readers into thinking that Casey’s comment about “the cause” was meant to indicate that he was heartened by his (in fact nonexistent) success on Substack:

“I’m able to live comfortably doing something I find enjoyable and fulfilling,” he wrote on his Substack in 2021. “The cause isn’t going anywhere.”

In reality — again, based on reading the post Katz didn’t give readers access to — exactly 200 words separate those two quotes. Now, different publications actually have different policies on quotes of the form “ ‘X,’ said/wrote Smith. ‘Y.’ ” In my experience, some require that X and Y to have actually occurred consecutively, while others allow you to pull Y from elsewhere. But clearly, you can’t do this if it significantly changes the context or meaning of X or Y. To illustrate the principle with an intentionally ridiculous example: say at one point in your interview with your source, Smith, he says “Nazis want to kill Jews.” Twenty minutes later, when you say you’re going to grab a Coke and ask him if he wants one, he says “Mmm, sounds great.” You obviously can’t then use the resulting transcript to generate the following line:

“Nazis want to kill Jews,” said Smith. “Mmm, sounds great.”

Katz’s presentation of these quotes is not quite on this level, but it’s also obviously not kosher. In context, Casey’s insistence that “The cause isn’t going anywhere” is basically the far-right equivalent of a call for his sad-sack readers to practice self-care and stop posting white nationalist stuff if they have mental or physical health problems to take care of first, or want to start a family. It has nothing to do with Substack. He’s clearly saying If you need a break, take one — our idiotic struggle to make America white again will be here when you get back.

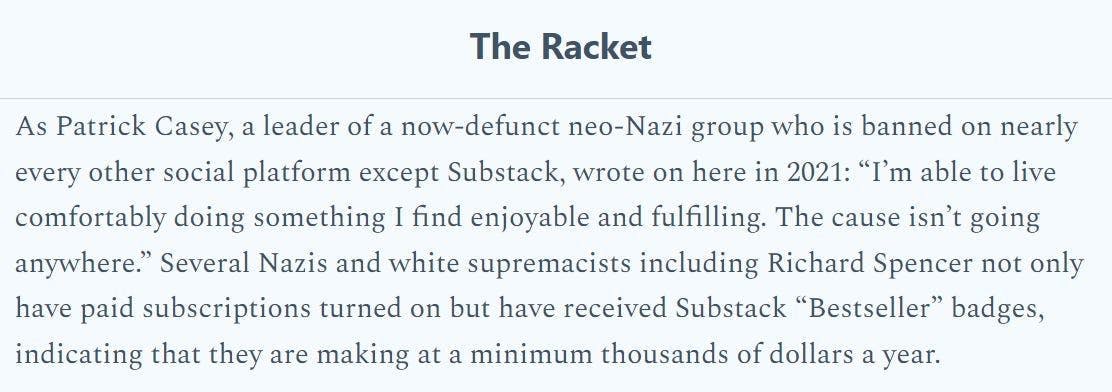

Naturally, given how internet games of Telephone work, the two parts of the quote got fully collapsed together, without “he wrote on his Substack in 2021” separating them, early on in the open letter that outraged Substackers signed and disseminated on their own publications. This only further fueled the idea that Casey, following the disbanding of his prior racist group and the major setback of being banished from Stripe, had been reinvigorated by Substack’s welcoming attitude toward his ilk:

As Patrick Casey, a leader of a now-defunct neo-Nazi group who is banned on nearly every other social platform except Substack, wrote on his Substack in 2021: “I’m able to live comfortably doing something I find enjoyable and fulfilling. The cause isn’t going anywhere.”

Katz was one of the many Substackers who both signed the original Google Doc letter and reposted it on his own Substack. His post was behind a paywall, so, with gritted teeth, I slapped down $6 for a one-month subscription (don’t worry — tax-deductible) to allow me to double-check that Katz himself disseminated the open letter in this exact form.

Sure enough, he did:

I guess the others who disseminated the open letter can be excused for collapsing the quotes in this manner. On the other hand, aren’t many of them journalists? Who are familiar with the basic norms of harvesting quotes? Who should fact-check claims before endorsing them with their names? Who should exhibit basic due diligence? Sorry, sorry — I’m being naive.

But in Katz’s case, as the guy who knew the full context of these quotes, you really can’t do this! No credible publication, other than the mangiest of tabloids, would find it acceptable to pull together different parts of a document that are separated by hundreds of words, especially when that severely distorts their context, in this manner. This is quite dishonest. It’s the sort of quote-fiddling that, if you’re a staffer at a major publication, gets you at best a very stern talking-to from your editor, if not a suspension or worse. We’ll see if Katz does the right thing and schedules a meeting with himself to discuss the ways in which he failed to adhere to his own standards. Hopefully, Katz will truly grill Katz about what Katz was thinking. Oh, to be a fly on the wall during that meeting!

In a world where basic journalistic and academic norms prevailed, the signatories of the letter would remove their names from it and/or insist it be edited, because as written, it is disseminating false information and a very misleading quote. They won’t do that, because then they’ll be accused of being “pro-Nazi,” and who wants that?

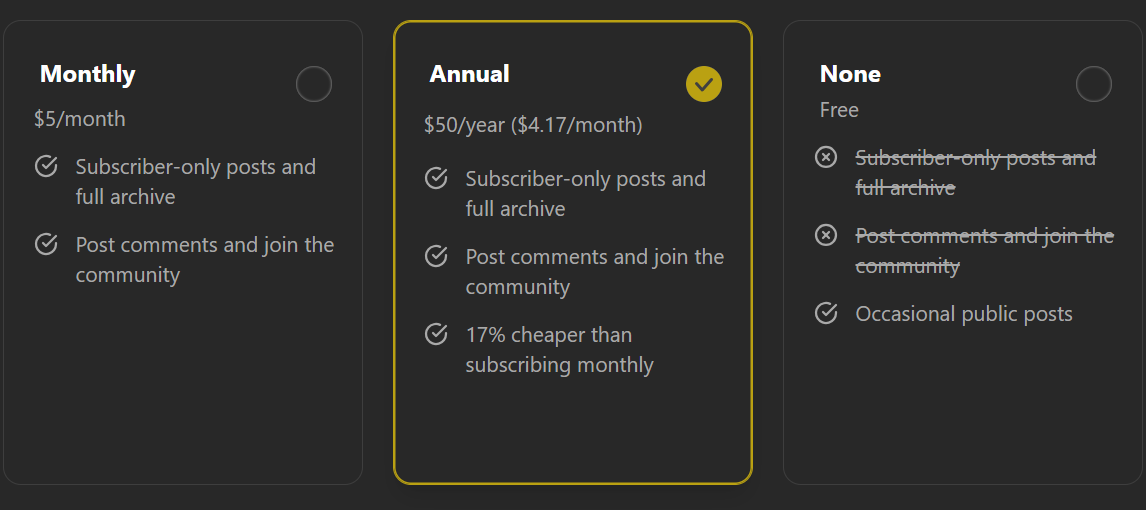

Now, for the sake of practicing transparency myself, I should note that today, in 2024, you apparently can pay for Patrick Casey’s newsletter (that’s a skip for me), an odd fact for Katz to have left out of his piece given that it bolsters his case that there are monetized white nationalists on Substack:

A source at Substack told me that the likely explanation is that Casey was unbanned by Stripe at some point. In our brief email exchange, Casey said he wasn’t sure how he got reinstated — “I just turned [paid subscriptions] on. That was it.” While Casey wouldn’t reveal how many paid subscribers he has, he said it is not a lot: “I don’t have many,” he explained. “My focus is on livestreaming. Substack is just a side thing. I enjoy using the platform, but I don’t see it becoming my main focus.”

Casey described his income from Substack as “negligible,” and in addition to the small listed subscriber count, Restoring Order has all the hallmarks of a newsletter that hasn’t caught on at all. Despite having been around since 2020, there’s almost no engagement. Even nine likes is unusual for one of his posts. It should go without saying that I’m not judging people, morally, on how many likes they get on Substack! I’m making a point about Katz being quite misleading about this particular individual’s popularity. Casey’s paid subscribers are in the single or double digits, the lack of the badge tells us. If I had to guess, based on the almost complete lack of engagement with his work on Substack, the 800 figure, and Casey’s own acknowledgment about the tininess of his revenue, I’d venture to guess he has closer to zero paid subscribers than 100. (Casey said Katz did not reach out to him for comment, which, if true, means Katz didn’t seek to confirm anything about Casey’s experiences with Substack.)

So Katz’s description of the Patrick Casey situation is riddled with false and misleading claims. On the whole, it is a fabricated story. It never should have been published by The Atlantic in that form.

I reached out to The Atlantic and to Katz about all this. “Thank you for the further, if unnecessary, confirmation that white nationalists are posting and making money on Substack,” replied Katz. “The rest of your claims here are either misleading or simply incorrect.” I asked him which of my claims were incorrect. “It’s Friday afternoon ahead of a long weekend,” he replied. “Don’t have time to help you right now, sorry.”

As for The Atlantic, late last night I got a response from a spokeswoman there:

Tonight we updated the piece (which you can see on the site) to point out the ambiguity in the Patrick Casey post that you referenced. The text of that section now reads: The extent to which this workaround—and Casey’s presence on Substack more generally—contributed to his livelihood is unclear. “I’m able to live comfortably doing something I find enjoyable and fulfilling,” he wrote on his Substack in 2021. “The cause isn’t going anywhere,” he declared in the same post.

Some additional context on background: Our fact checkers ran our description of Casey’s effort to work around the Stripe ban past Substack before publication, and asked for comment, which we did not receive. [emphasis in the original]

The spokeswoman subsequently gave me permission to share the second paragraph and attribute it to her.

I guess something is better than nothing, but I don’t think this really fixes the issues I raised. Here’s how the segment currently looks, with the new stuff in bold:

The platform has shown a surprising tolerance for extremists who circumvent its published rules. Patrick Casey, a leader of Identity Evropa, a defunct neo-Nazi group, had been banned from Twitter and TikTok and suspended from YouTube after running afoul of those platforms’ terms of service. (Elon Musk, Twitter’s owner, subsequently announced an “amnesty” that restored Casey’s account, among others.) Perhaps most damagingly to a content creator, Stripe had prohibited Casey from using its services.

But Substack was willing to let a white supremacist get back on his feet. Casey launched a free Substack newsletter soon after the 2020 election. Months later, he set up a paywall, getting around Stripe’s ban by involving a third-party payment processor. The extent to which this workaround—and Casey’s presence on Substack more generally—contributed to his livelihood is unclear. “I’m able to live comfortably doing something I find enjoyable and fulfilling,” he wrote on his Substack in 2021. “The cause isn’t going anywhere,” he declared in the same post. Casey’s newsletter remains active; through Substack’s recommendations feature, he promotes seven other white-nationalist and extremist publications, one of which has a Substack “bestseller” badge.

All the key, false assertions are still there: the passage still claims that Substack tolerated circumvention of its published rules in this instance and that Substack got Casey “back on his feet.” It’s still heavily implied that Casey set up a paywall on Substack. There’s no mention that his “The cause isn’t going anywhere” remark has nothing to do with Substack. On top of that, in my note to The Atlantic, I pointed out that Casey had told me directly that he had made a “negligible” amount of money on Substack. It doesn’t appear the magazine attempted to contact him to ask about any of this. It’s not that it’s unclear whether Casey made a lot of money on Substack; rather, we have multiple lines of evidence, including the published statistics and Casey’s own say-so, strongly suggesting he didn’t. This isn’t a mystery and I don’t think The Atlantic should present it as one. I think the errors in this passage warrant correction, not just an “update.”

I also told The Atlantic that I had confirmed with Substack that the claim that anyone “restricted from making money on Substack” is banned from using the platform is false. The Atlantic simply ignored that part of my critique and the live version of the article continues to make that claim.

As for “Our fact checkers ran our description of Casey’s effort to work around the Stripe ban past Substack before publication, and asked for comment, which we did not receive,” you know what would have been a good way to fact-check whether or not Casey attempted to engage in a verboten Stripe-ban workaround on Substack? By reading his own post, which explained exactly what he was doing at the time! Substack may not have responded to the fact-checkers’ inquiries, but 1) The Atlantic shouldn’t have needed information from the company to ascertain the truth of the matter here; and 2) it’s unsurprising that Substack wouldn’t want to provide any details about its dealings with one of its users, even a white nationalist — especially one who doesn’t appear to have violated any of the rules.

With the exception of a perfunctory nod or two, Katz doesn’t really grapple with the question of how Substack should moderate its content, if it is to replace its present, very liberal approach. As Substacker and frequent must-read Ken White, a.k.a. Popehat, noted in an article that was generally sympathetic to Katz’s claims, moderation is hard, and “It’s notable that the critics of Substack’s ‘Nazi problem’ do not offer a specific definition of what content they’d moderate.” This is an especially important fact to grapple with in light of the obvious fact that these days people are constantly trying to deplatform their political enemies for ostensible thoughtcrimes far short of Actual Nazism. No one can credibly deny this: White and Newton both noted it in their coverage of this controversy, as did Katz himself (“partisans of all stripes have an incentive to accuse their opponents of being extremists in an effort to silence them”), as did Freddie deBoer in a post ridiculing this whole thing.

More conservative approaches to content moderation undeniably bring their own problems — serious ones. And those who critique liberal approaches to policing speech often have little to offer in the way of workable alternatives. This is not a new problem for left-of-center critics of liberal free speech laws and norms: in my experience, they have tremendous difficulty thinking beyond “Let’s ban the things that offend us.” They don’t actually understand the speech ramifications of existing and compromising in a cacophonously pluralistic society, perhaps because they often live and work in nearly impermeable bubbles of like-minded peers.

It’s easy to understand the problems inherent to the approaches Substack critics are clamoring for: just look at the guidelines actually on offer elsewhere. Take one of the successful Substackers departing the site in a huff: Rusty Foster of Today in Tabs. His January 3 post reads, in part, that he spent some of the holiday break “extracting Tabs from the Nazi bar and setting up our new home here on Beehiiv. Yesterday on a Google Meet Beehiiv CEO Tyler Denk effortlessly cleared the lowest bar in content moderation by saying with his own voice ‘Nazis are banned.’ He didn’t even appear to be sweating. And he said that goes for anti-trans content as well! It was wild seeing a tech executive just casually making the right decisions one after another.”

Thank God we have individuals like Tyler Denk who can effortlessly decide — without even sweating! — which sort of speech should and shouldn’t be allowed. I’m extremely thankful for such individuals and aspire to their level of moral clarity.

To further enlighten and better myself, I headed over to Beehiiv’s Terms of Use in the hopes of learning a thing or two. Here are the “Content Standards” to which Foster, not to mention his fellow émigré Jonathan M. Katz, will now be subjected:

Content Standards

These content standards apply to any and all content published to beehiiv. Content must in their entirety comply with all applicable federal, state, local, and international laws and regulations. Without limiting the foregoing, content must not:

Boy, does Beehiiv restrict a lot of speech if you read its rules literally! You better not set up shop there if you intend to write anything that is “indecent,” “harassing,” “inflammatory, or otherwise objectionable.” (Luckily there’s 100% societal consensus on what these terms mean and which speech acts qualify, so I’m sure there won’t be any issues.) Similarly, you shouldn’t publish anything that would “[b]e likely to deceive any person.” How likely is likely? How deceptive is deceptive? Doesn’t say. Finally, neither Foster nor Katz nor anyone else on Beehiiv can write anything that will “[c]ause annoyance, inconvenience, or needless anxiety or be likely to upset, embarrass, alarm, or annoy any other person.”

If you’re a writer, why would you want to migrate to such a censorious platform? Especially if you’re the kind of writer — a Rusty Foster type — who produces a lot of work that “cause[s] annoyance”? I quickly found this post, for example, and it caused me annoyance because it’s so smarmy and lazy and stupid. I AM CALLING THE CONTENT POLICE. As for Katz, if he plans on publishing a Beehiiv post in which he endorses the celebration of my death with an alcoholic beverage, he could get in trouble, because it would certainly cause me “needless anxiety.”

The obvious answer to the “Why go there?” question is that Foster and Katz don’t actually have to worry about Beehiiv taking action against them. They have Good Politics, and these guidelines will be applied only to those who have Bad Politics, with possible exceptions in the most extreme cases of death threats and so on. Beehiiv, I predict, will utterly fail to enforce its own content guidelines. It will have to, or it will swiftly cease to exist as anything but a blog for posting photos of kittens. But then that business model will collapse, because some people are allergic to cats and will report those posts as having caused them “needless anxiety.”

Along those same lines, Katie Herzog and I got an email from someone at Supporting Cast, attempting to capitalize off this fauxtroversy:

Dear Katie and Jesse,

I’m reaching out because I imagine you share my concerns about recent developments regarding Substack’s content policies and their decision to host and handle payments for users promoting extreme views, including those associated with hate groups.

Meanwhile, at Supporting Cast, we believe in fostering a safe and inclusive environment where diverse voices can thrive while respecting the boundaries of responsible content moderation; check out our acceptable use policy if you’re curious to learn more.

I did as the kind gentleman directed, and I found this paragraph:

Engaging in activities that are, or transmitting through the Services any information that is, libelous, slanderous, or otherwise defamatory; discriminatory based on race, ethnicity, sex, gender identity, religion, nationality, disability, sexual orientation, or age; or otherwise malicious, abusive, harassing, threatening, or harmful to any person or entity.

“Otherwise malicious, abusive, harassing, threatening, or harmful to any person or entity” — what does that mean? What is “malicious”? Hell, what is “abusive”? I have been told I am acting “abusively” because I retweeted someone and made fun of what they said. Will Supporting Cast shut down our podcast if we make fun of someone’s bad tweet? They’d certainly be within their rights to do so based on this language, and based on how many people scream ABUSE! when one of their friends gets made fun of for a bad tweet. Not only that, but if we quote someone saying something that meets these impossibly loose standards, that would be considered a violation via the “transmitted through the Services” clause!

As a final example, take the platform Newton fled to because he was so outraged by the Nazis. Ghost is both a platform of sorts and an open-source software package. The former is moderated, but anyone is free to download the software and set up their own blog or newsletter arguing that, say, Jews secretly control Taylor Swift’s live setlists. Ghost has no way to moderate that content, even if it violates its published guidelines.

Newton responded to this objection in the FAQ section of his prickishly sanctimonious super brave goodbye-to-Substack post:

Aren’t you going to have this exact same problem on Ghost, or wherever else you host your website?

As open-source software, Ghost is almost certainly used to publish a bunch of things we disagree with and find offensive. But it differs from Substack in some important respects.

One, its terms of service ban content that “is violent or threatening or promotes violence or actions that are threatening to any other person.” Ghost founder and CEO John O’Nolan committed to us that Ghost’s hosted service will remove pro-Nazi content, full stop. If nothing else, that’s further than Substack will go, and makes Ghost a better intermediate home for Platformer than our current one.

Two, Ghost tells us it has no plans to build the recommendation infrastructure Substack has. It does not seek to be a social network. Instead, it seeks only to build good, solid infrastructure for internet businesses. That means that even if Nazis were able to set up shop here, they would be denied access to the growth infrastructure that Substack provides them. Among other benefits, that means that there is nowhere on Ghost where their content will appear next to Platformer. [formatting in the original]

Let’s click on that ToS link. Ghost bans content that:

Again — so much speech is potentially banned! “Individual’s rights to privacy” means a thousand different things in a thousand different jurisdictions. Details are not provided. Also banned are “fraudulent, false, misleading, deceptive, untruthful or inaccurate” claims. Finally, we have an easy answer as to who gets to decide what’s true and false: a technology platform! Can’t see any potential problems there. So if you say Jacob Blake was unarmed on Ghost, you can get suspended or banned. Doesn’t that seem. . . excessive? And how in God’s name can any individual, least of all a tech bro, fairly determine what is “misleading” for others? This is a source of constant societal disagreement! I think the ubiquitous claim that the evidence for youth gender medicine is strong, is, by any reasonable understanding of the relevant concepts and standards, deeply “misleading.” But I cannot in my wildest dreams imagine calling for people who recite this mantra to be banned from their platforms, or to even have the claims pulled down against their will. That’s despotic and completely antithetical to an open society with real discourse. It’s absolutely menacing to put so much power in tech platforms’ hands, and it’s deranged that my saying so is now seen by many as a right-coded argument.

Just to press the point a bit further, I hope there aren’t any advocates for the Palestinian people on Ghost who believe in the power of civil disobedience, because any such sentiments are strictly and obviously verboten there. This isn’t even a close call: Ghost bans content that “violates, or encourages any conduct that would violate, any applicable law or regulation[.]” So “Let’s block the George Washington Bridge to protest Israel’s bombardment of Gaza” is absolutely banned by Ghost’s terms of service. Now, do I personally think blocking roads and bridges, inconveniencing a bunch of people, is anything but an asinine and self-indulgent form of activism? Of course not. But do I want people censored from calling for it? Of course not! That’s insane! Similarly, I hope no one who is into doing shrooms is on Ghost, because a statement like “Even if shrooms are criminalized in your jurisdiction, you should try them — they’ll open your mind” could get you kicked off of Ghost, as could, again, calls for civil disobedience: you’re not allowed to say “A rich person should get arrested for possession of shrooms, hire a fancy lawyer, and then draw as much attention as possible to the case so as to advocate for saner laws on psychedelics.”

Ghost also bans content that “promotes. . . abuse or harm against any individual or group.” I’m not trying to be cute here, but if I say that an arms manufacturer’s civilian market products should be boycotted, then I am, technically speaking, violating Ghost’s policies, because I would be promoting harm (lost revenue) against a group (KidKill Inc.).

Now, to repeat myself, Ghost isn’t going to crack down on any of this. Instead, Ghost will simply and chronically decline to enforce its own standards, with a few exceptions. It is quite unlikely these exceptions will be evenly applied or will not reflect the political biases of, you know, the people who run Ghost. Whether or not I’m correct about this, just think about this from the point of view of writers and podcasters on Ghost: they’re in a situation in which as soon as they say anything remotely interesting, they are inevitably breaking multiple rules of the platform, except these rules aren’t ever enforced. Is that conducive to open-minded inquiry and interesting thought? Seems rather Damoclean to me.

Look, at the end of the day, all these platforms say they reserve the right to remove any content for any reason, including Substack. That’s the risk we all run by tying up our livelihoods in third-party platforms and payment processors. But Substack is clear and consistent about its standards, and while it allows Nazis who don’t credibly threaten violence, it also allows authors to call for civil disobedience, to advocate passionately for Palestinians, to say whatever non-legally-defamatory thing they want about arms manufacturers, and to engage in all sorts of other discourse very obviously banned, to various extent, by Beehiiv, Supporting Cast, and Ghost. This seems like an obvious trade-off for anyone who thinks they might write or say something controversial or surprising at some point, but I understand that’s not exactly in fashion at the moment among the sorts of people leading the charge against Substack.

This whole moral panic has just been so myopic, so devoid of adult conversation about what it means to actually crack down on speech acts, and so driven by dishonest and shoddy journalism, that it’s quite hard to take it seriously. I’m sad it had any effect whatsoever, though I suspect it will leave no lasting mark. I wish Casey Newton and Jonathan M. Katz and Rusty Foster and so many others the best in their heroic efforts to fight fascism by hermetically sealing themselves off from it.

Questions? Comments? Emails about how you have here in your hand a list of 205 names that were made known to Substack as being Nazis and who nevertheless are still posting to Substack? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. The lead image was ChatGPT’s output in response to the prompt “wide format, an image of a moral panic.”

Substack does ban pornography and self-, other-, and animal-harm content, but I’m guessing that can be chalked up more to legal problems and the moderation headaches the threat of said problems bring than ideological stances. For what it’s worth, I did reach out to a couple Substack higher-ups to ask about these exceptions, but they didn’t want to talk about them on the record.

0 free articles left