A New Introduction from The Authors

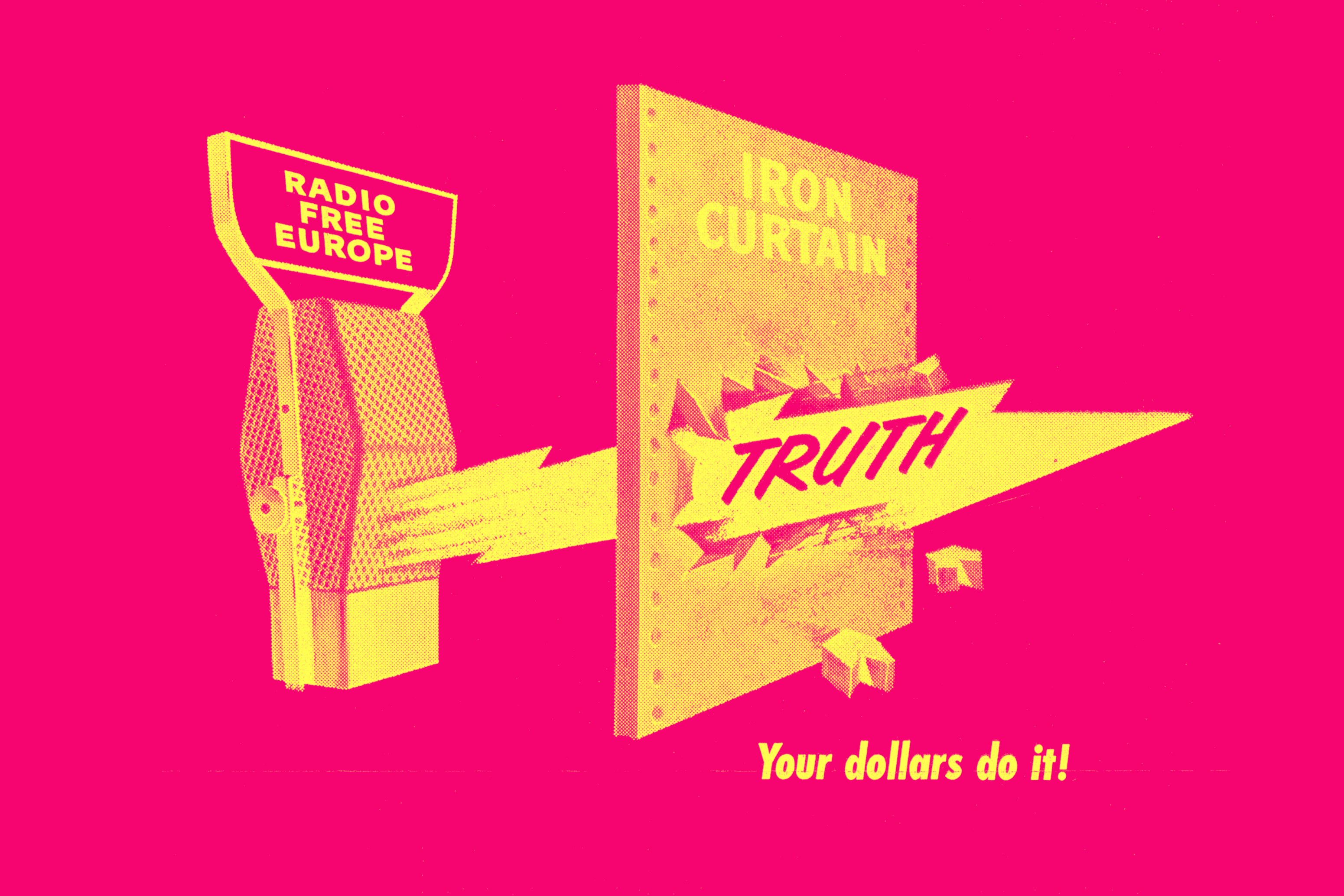

This article was originally published in August 2024, in the aftermath of the tragic Southport murders in the UK, the riots that followed, and the UK government’s shocking, if predictable, response of aggressively prosecuting speech offences on the part of outraged native Brits. Our commentary highlighted that X (formerly Twitter) was serving as a kind of contemporary Radio Free Europe in providing Brits with an uncensored and uncensorable source of truth amidst an avalanche of propaganda from their own government.

In the 18 months since, the UK’s censorship apparatus has only intensified its work. The British state has not slowed down in prosecuting speech offences that violate its preferred narrative. In an astonishing twist, the UK has even taken its internet censorship regime global, seeking to use the Online Safety Act to censor American companies with no UK presence — which co-author Preston Byrne has fought directly in his capacity as a lawyer, representing all of the Online Safety Act’s first crop of American targets pro bono, bringing litigation against the UK’s communications regulator in U.S. federal court, and writing a U.S. censorship shield statute which is on the verge of introduction in the State of Wyoming. At the same time, members of the U.S. Senate are promising to introduce shield laws of their own and the U.S. State department vows that America will respond.

The crescendo of this madness arrived as the U.S. State Department threatened to sanctioned two British nationals and the Labour government, who were using the pretext of scandalous Grok AI image requests to re-establish the UK censorship regime’s credibility by threatening to shut down X in the UK altogether.

We feel this perfectly vindicates our original argument and highlights the importance of the themes we identified: X is virtually the only avenue for uncensored and coordinated dissent against the British establishment. It is unsurprising the conflict has reached this point. With an American federal government response to the UK’s censorship brewing, it will be fascinating to watch what happens next.

—Allen Farrington & Preston Byrne, January 2026

Anyone with access to the internet will be aware of the recent social unrest in Britain. Uncontroversially, individuals who rioted have found themselves on the receiving end of a harsh and swift law enforcement response. Controversially, individuals speaking about the riots — both at the protests and online — have found themselves in trouble as well.

In the United States, citizens are free to nonviolently express any opinion, in more or less any form. We can offend, insult, shock, even verbally abuse. We can express support for groups that commit, or have committed, violence. We can even say “hateful” things, because, as the U.S. Supreme Court said in Matal v. Tam (2017), “the proudest boast of our free speech jurisprudence is that we protect the freedom to express ‘the thought that we hate.’”

Critics of American-style free speech describe it as “free speech absolutism,” but consistently misunderstand, and often misrepresent, what American free speech really entails. It doesn’t mean allowing threats, direct incitements, or solicitations to commit a crime — these are illegal. “Free speech” means simply that there’s a powerful legal presumption that the government cannot police nonviolently expressed opinions, even in extreme cases where those opinions advocate for or express support for violence, but only to the extent that the expression of those opinions does not constitute active participation in a criminal act. No more, no less.