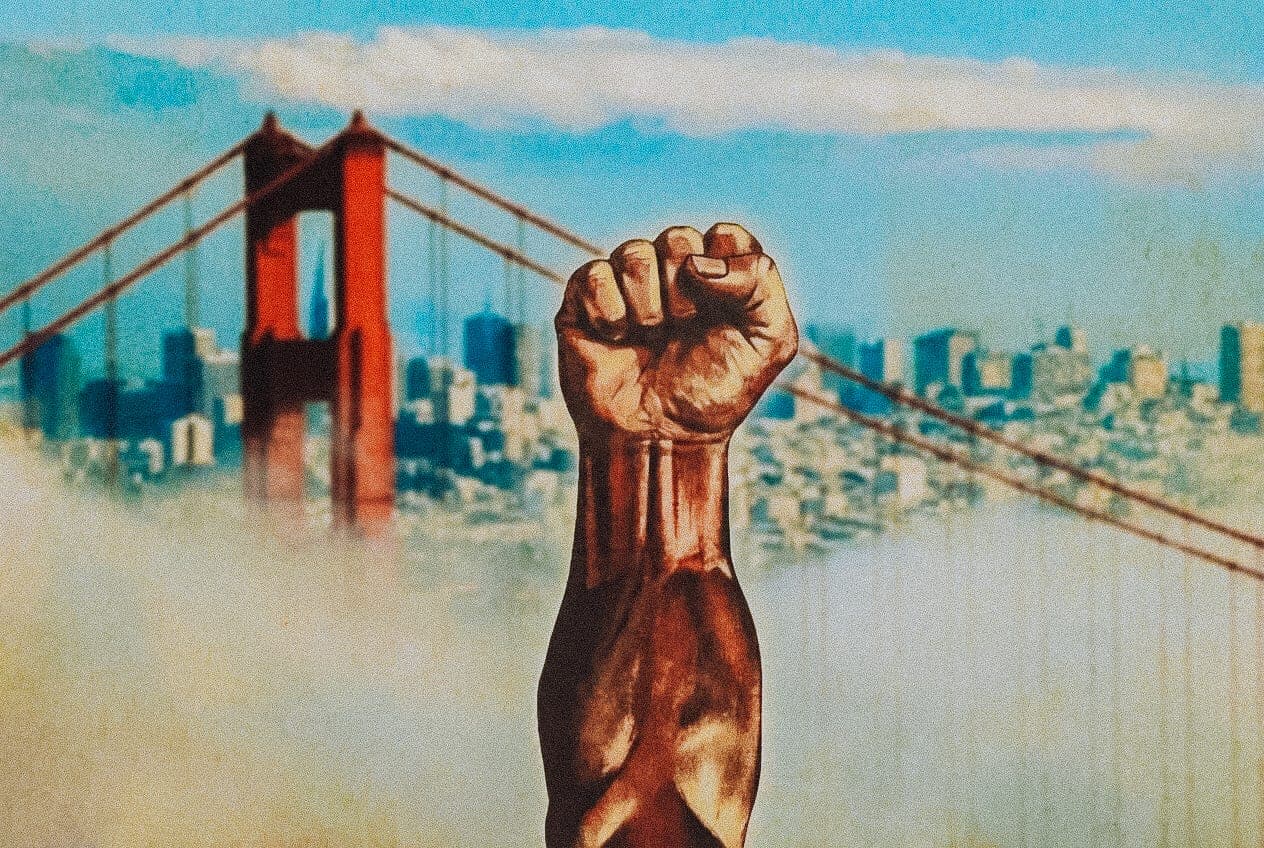

SF Really Wants To Give Black People $5M ChecksDec 20

the city's reparations scheme is dreaming big, delivering nothing, and derailing city funds

Mar 26, 2024

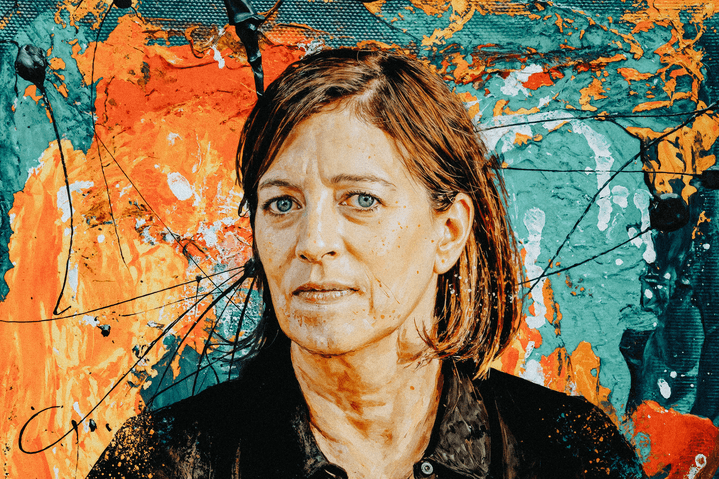

Jo Boaler, a Stanford professor of math education, is arguably the person most responsible for the new California Math Framework, a set of curriculum recommendations that advocate against teaching most middle-schoolers algebra in the name of equity.

Though she advocates for these changes in the public school system, she's sent her own children to a $48,000-a-year private school that teaches its middle schoolers algebra, and charged an underfunded school district $5,000 an hour for her consulting services.

An anonymous 100-page complaint recently documented over 30 claims of alleged citation misrepresentation in her research — the very research that underpins the CMF.

Jo Boaler, a Stanford professor of mathematics education, is arguably the person most responsible for the new California Math Framework (CMF), a newly approved set of curricular guidance for teachers across the state’s more than 950 public school districts. These guidelines, which are non-binding but help shape instructional materials and practice, suggest delaying instruction of Algebra I until high school and teaching fuzzy “data science” courses as alternatives to calculus in the name of ensuring “equity.” The CMF has long been accused of distorting research to fit its policy agenda, but last week it got hit with what might be its most damning blow yet: a 100-page, well-sourced document published by an anonymous complainant alleging that many of the misrepresented citations throughout the CMF can be traced directly back to Boaler.

Though some of the specific allegations are new, the complainant’s conclusion — that Boaler has “engaged in reckless disregard for accuracy” throughout her career — won't be surprising to those familiar with her track record. Besides routinely misrepresenting citations for decades, Boaler also has a history of deceptively presenting her professional credentials, charging underperforming schools exorbitant consulting fees, and pushing to water-down public school courses while placing her own children in elite private schools.

Boaler first made a name for herself in the mid-2000s by advocating against “tracking” — a system designed to allow high-performing students to be appropriately challenged and underperforming students to receive appropriate support — and instead promoting “heterogeneous classes,” where students’ demonstrated math ability is ignored and all are taught the same content. For years, she’s had the ear of administrators and policy wonks eager to reform teaching practices in a state where over 65% of students aren’t meeting grade-level math standards.