Year in Wires, 2025Dec 26

in january 2025 the whole world changed — a look back at all the bangers, as pirate wires covered the intersection of politics, technology, and culture

Feb 18, 2025

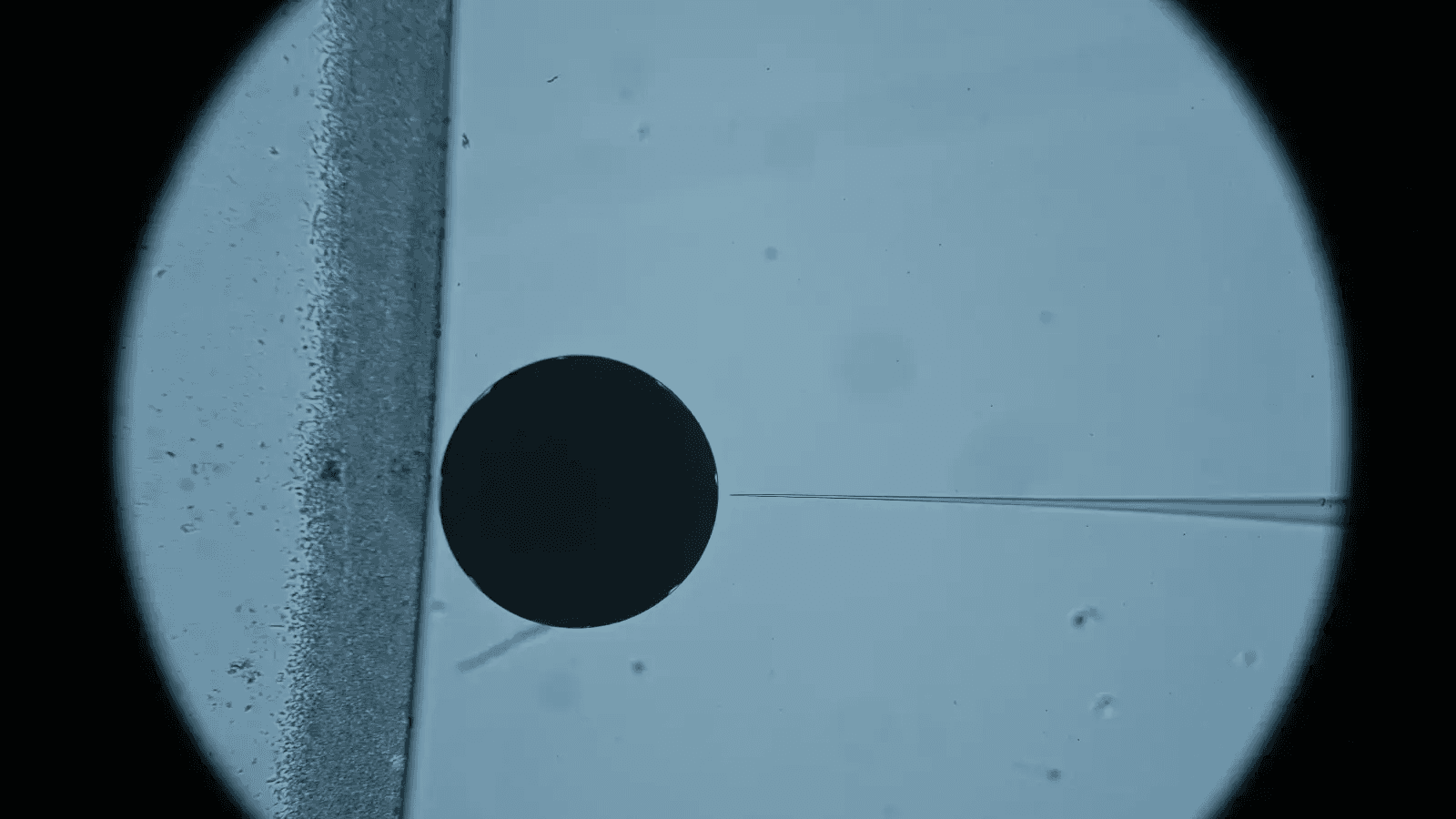

The Los Angeles Project (LAP), a venture-backed biotech startup that’s been operating quietly for the past year, comes out of stealth today. Its pre-seed round was funded by 1517 and other undisclosed investors. Josie Zayner and Cathy Tie, the company’s co-founders, have been building a high-throughput gene-editing platform and knowledge database focused on the genetic modification of animal embryos. One of the company’s most exciting, and eccentric, objectives? “I want to build a unicorn,” Cathy told me. In Josie’s words, LAP is a “generational company creating a new lineage of biotech” and, hopefully, “a new lineage of life.”

The company, by constructing an automated system for genetically modifying animal embryos at scale, will master the science of manipulating cellular and genetic material, which Josie characterized as “alien technology.” Practically, this entails starting with small animals like cats and rabbits, training their systems on the resulting data, and eventually taking on more ambitious projects like xenomedicine (using biological materials from animals to treat human medical conditions) and, of course, the creation of the prized unicorn.

Fittingly, Josie Zayner and Cathy Tie are inured to hard problems and operating against the status quo. Josie is a biophysicist who earned her PhD from the University of Chicago and worked at NASA to engineer plastic-eating bacteria for Mars missions. She previously founded a company that sells DIY genetic engineering kits to amateurs, performed a full-body microbiome transplant documented by The New York Times, and famously injected herself with a CRISPR solution meant to modify a gene that controls muscle growth. She also created (and took) a DNA-based COVID vaccine on livestream in 2020 and gave herself temporary breasts with an experimental injection (later coming out as transgender in 2022).