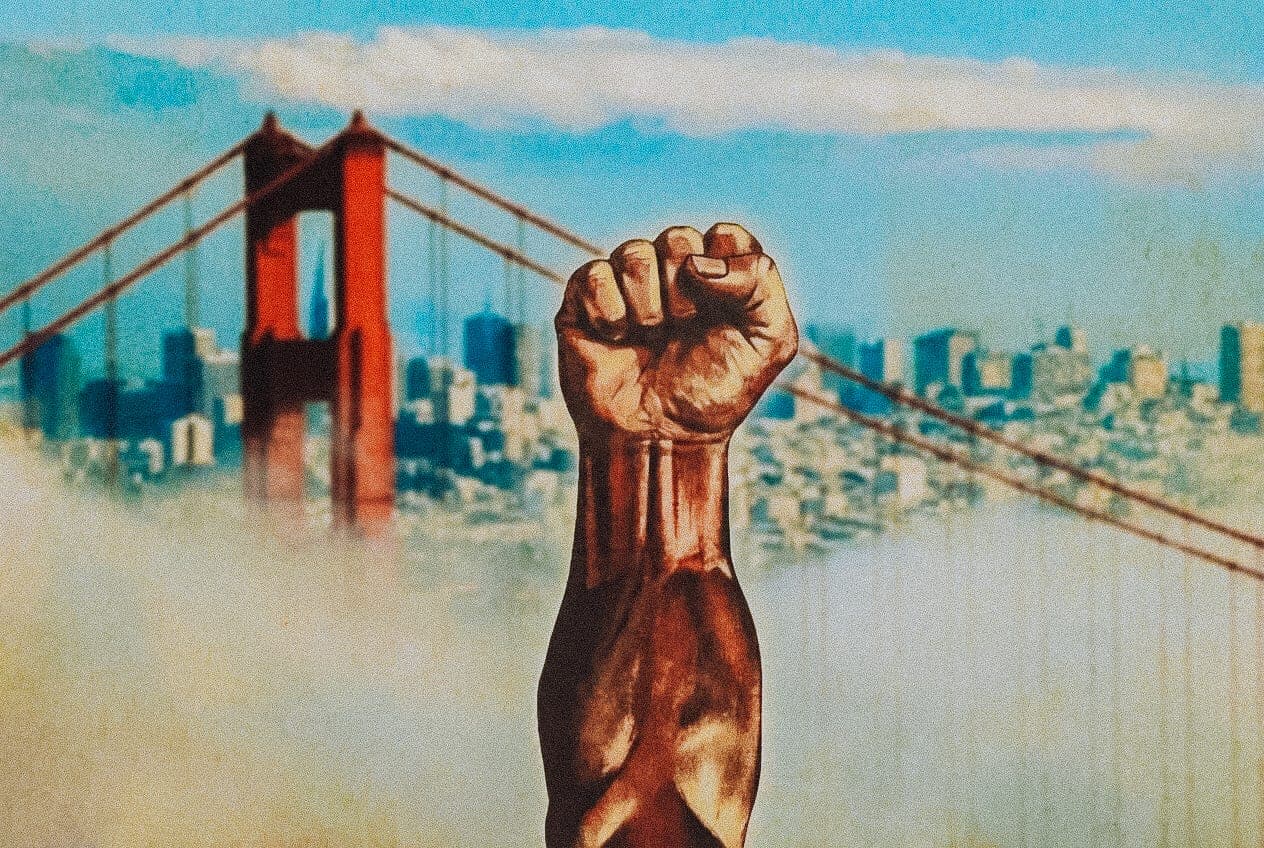

SF Really Wants To Give Black People $5M ChecksDec 20

the city's reparations scheme is dreaming big, delivering nothing, and derailing city funds

Apr 3, 2023

It’s been a busy past few weeks in France. Days of strikes and violent protests spurred by a pension reform have left the country’s cities strewn with uncollected trash piles, smashed storefront windows, and firebombed cars. Most in the media and general public have little on their minds beyond the now-infamous “réforme des retraites,” which seeks to raise the national retirement age from 62 to 64 and slightly restructure pension distribution — measures deemed “painful but necessary” by French president Emmanuel Macron and “abominable and injust” by the opposition. Fortunately, between near-daily no-confidence votes and shouting matches about the excesses of their ‘tyrannical’ president, members of the country’s National Assembly (the lower chamber of parliament) have managed to squeeze in some time to discuss other legislation, including a broad package of laws related to the administration and security of the 2024 Paris Olympics, passed on March 24 by a 59-14 preliminary vote.

The National Assembly’s decision to greenlight the bill followed months of debate about one section in particular — Article 7 — which permits the use of AI-assisted video surveillance technology by law enforcement during and up to six months after the Games. The article has been subject to an intense international campaign demanding its rejection; Amnesty International warned that its provisions would turn France into a “dystopian surveillance state,” and an open letter spearheaded by the Netherlands-based European Center for Not-for-Profit Law denounced the “structural discrimination” and “over-criminalization of racial, ethnic and religious minorities” that, it claimed, inevitably arise when using AI-powered algorithms to fight crime. In the National Assembly, lawmakers proposed over 770 amendments to Article 7 alone, and discussion over these lasted for a couple of days until everyone abruptly lost interest. Squabbling about pension reform resumed, and only 73 of the almost 600 members of the lower chamber showed up to the preliminary vote on the bill. As Félix Tréguer, a member of the French privacy watchdog association La Quadrature du Net put it: “The largest acceleration of algorithmic governance [in France]…was approved in almost complete indifference and against the backdrop of social upheaval.”

But the story of Article 7 is not just about an eclectic moment in French politics; it is about what happens when the concerns of privacy watchdogs, tech-incompetent politicians, and a disaffected public converge on novel technologies that enable powerful uses and abuses. Let’s dive in.