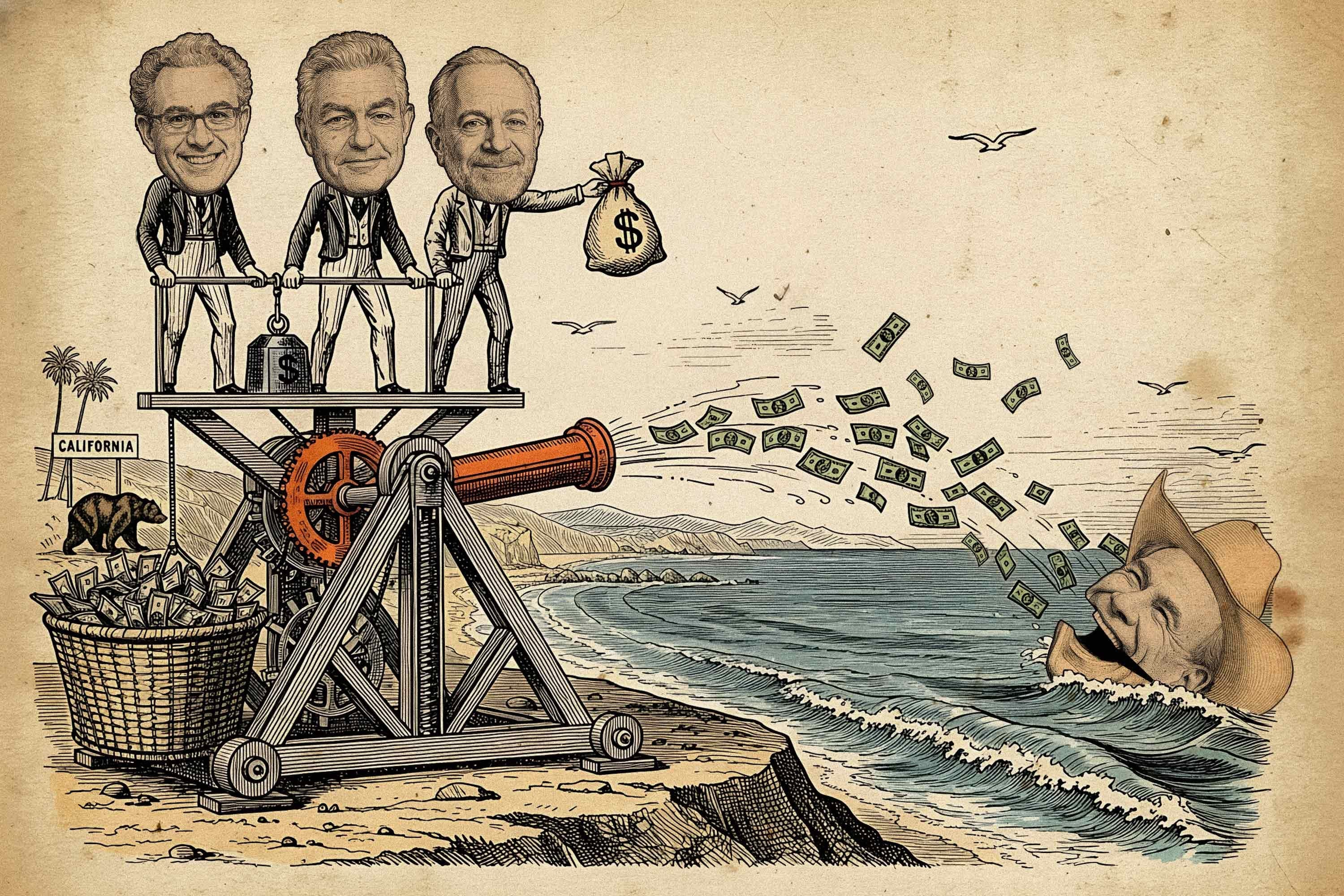

Meet the Architects of California’s Billionaire TaxFeb 13

the union who sponsored the proposal is trying to scale. the academics who wrote and influenced it are trying to counter billionaires' control over 'prevailing ideology'

Jul 2, 2024

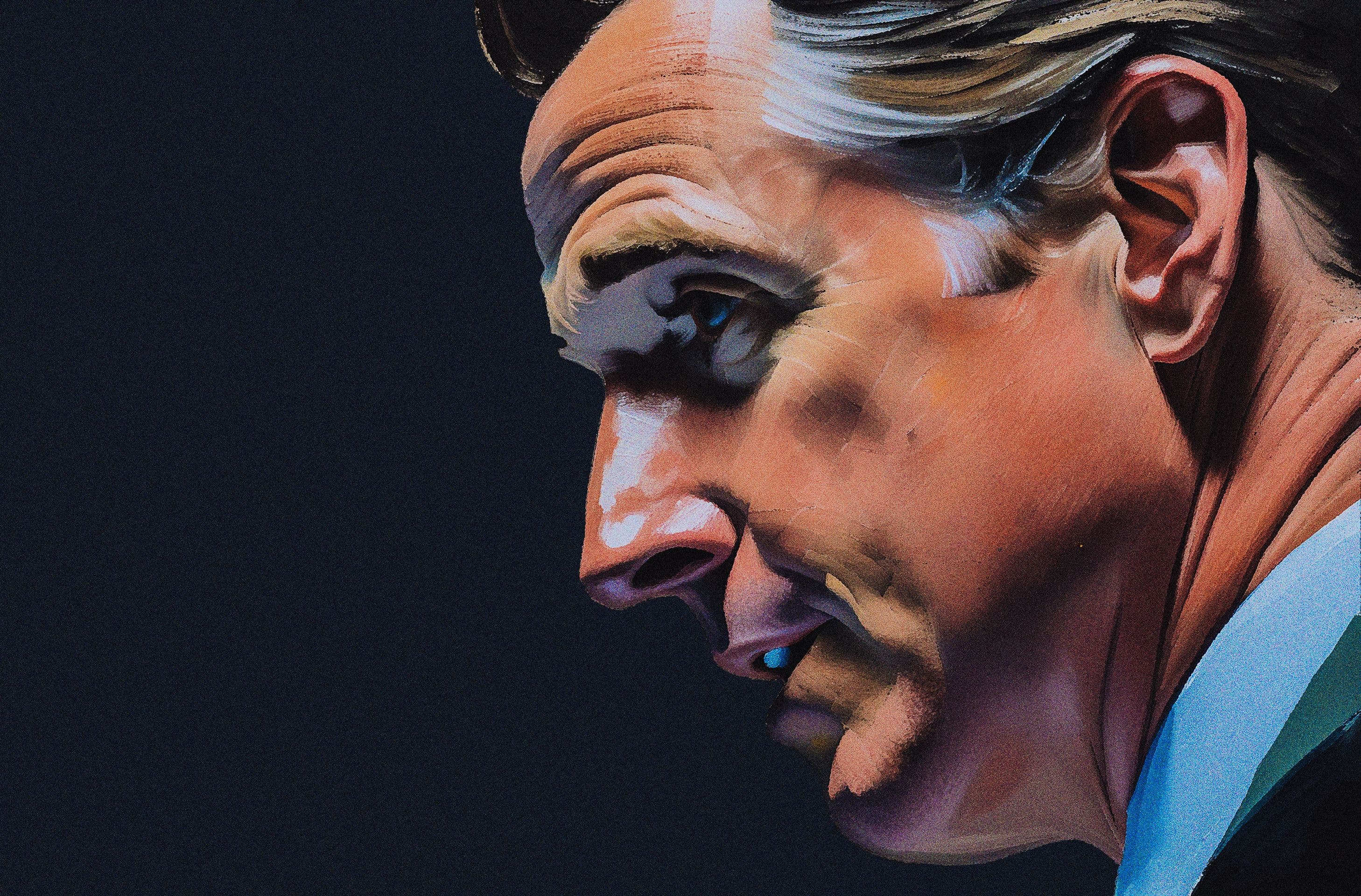

Last week, Governor Newsom and state legislators agreed to a balanced budget for California’s upcoming fiscal year, closing the multibillion-dollar deficit that has hung over the state for months. Despite eliminating thousands of vacant government jobs, and making deep cuts to prison funding and affordable housing programs, the approved $288 billion spending plan appears unlikely to resolve the structural revenue and spending concerns that led the state off a fiscal cliff in the first place. Newsom’s office’s own projections, which are often rosier than those of the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office, already suggest California will face a deficit exceeding $36 billion in FY 2025-26.

The Governor made good on his promise to not raise taxes this time around. But the approved budget retains billions of dollars in funding for the recent expansion of free healthcare and in-home supportive services to low-income illegal immigrants, the state’s disastrous high-speed rail money pit, and a multibillion-dollar homeless services industry recently found to not consistently track program spending or results. Worse, around 36% of the deficit was closed by using gimmicky one-time spending deferrals or transferring about half of the state’s “rainy day” reserve fund to its general fund. The latter is highly unusual and required Newsom declare a formal “budget emergency,” suspending a constitutional rule that precludes such transfers, while the former simply kicks the can down the road.

And this is to say nothing of the state’s over $600 billion in public employee pension debt, of which $150 billion is unfunded.