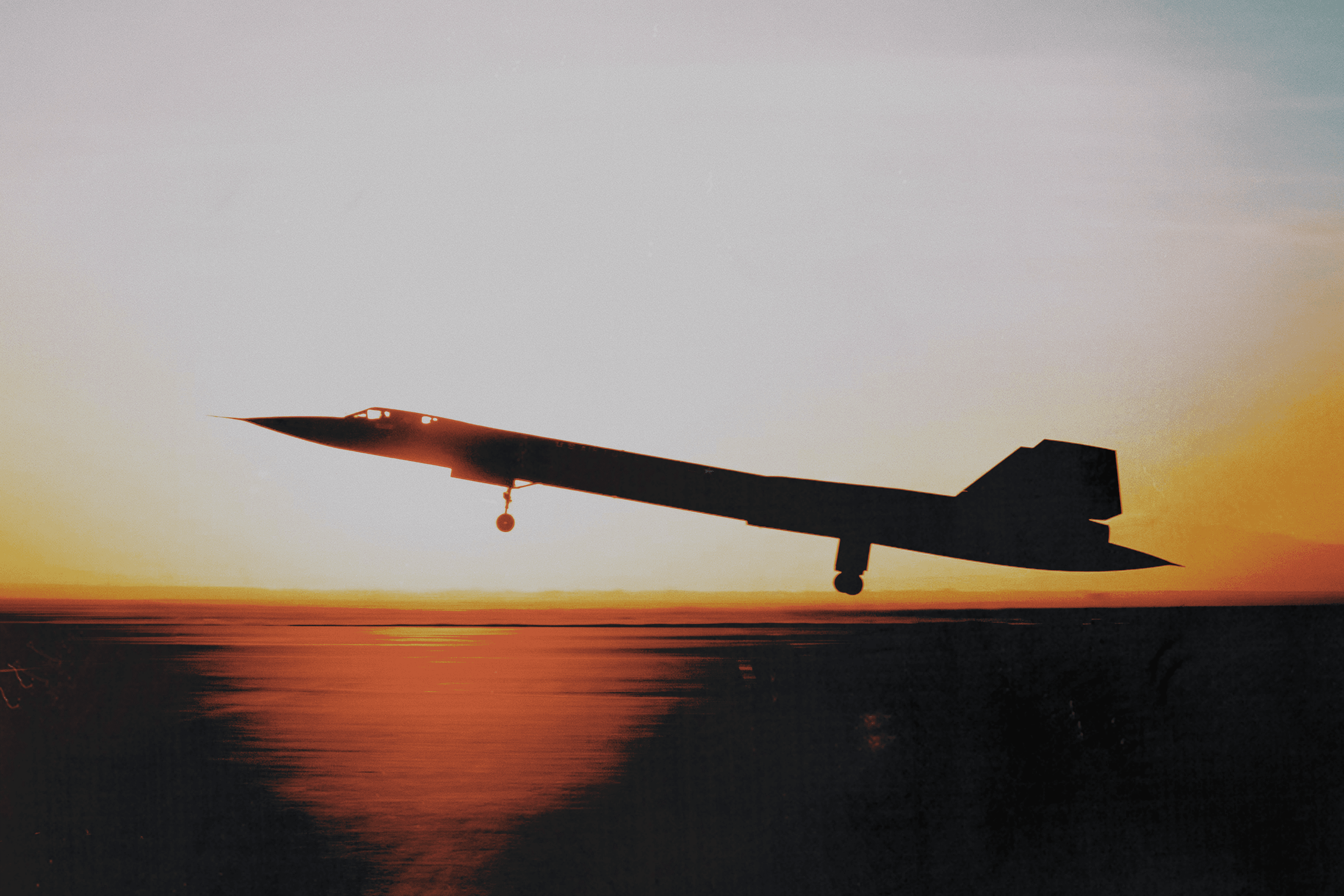

In the 70s and 80s, the SR-71 Blackbird — an advanced long-range reconnaissance aircraft developed by Lockheed's Skunk Works division under the direction of lead engineer Kelly Johnson — flew at speeds over Mach 3 (2,200 mph/ 3,540 km/h) at altitudes higher than 85,000 feet to reconnoiter and surveil enemy positions in the Soviet Union, Vietnam, North Korea, Middle East, China, Cuba, and anywhere else in the world, as needed. The jet was literally impossible to take down: no fighter aircraft or surface-to-air missile system could catch or intercept it, giving it free reign over hostile territory.

In the SR-71 era, the United States could track the enemy’s every move. This not only afforded us a massive advantage in real-time intelligence and operational flexibility, but was a powerful deterrent — the adversary knew we were watching, thus were discouraged from aggressive actions, and less likely to conduct surprise attacks. For the US, the SR-71 was an asymmetric advantage.

As a founder or startup leader, your goal is — obviously — to win at a game that matters. Not the little battles along the way, but the war that drives impact at massive scale. At my company Hermeus, the game we are playing is an ambitious endeavor to do what even the great Kelly Johnson couldn’t: deliver autonomous Mach 5 airplanes to the Department of Defense and eventually Mach 5 commercial passenger aircraft to shrink the world. The challenges we’ve faced building the company over the past five years have formed how I think about strategy more than any experience in my life. The core kernel of our plan to win has become as clear as day to me: asymmetry.